Dance Dance Rebellion

The COVID pandemic has set off a harsh trajectory of events, which continue to shed light on a global health crisis that is widening racial inequality and sharply increasing poverty. Long-held practices of police brutality are escalating while public services are dwindling and leaving people with unavoidable, impossible-to-answer dilemmas about their survival.

Rajikh Hayes, a Baltimore activist, explained this predicament when he was interviewed for The New York Times. Asked about concerns of the virus spreading in the Black Lives Matter rallies, he responded, “It’s really a simple question: ‘Am I going to let a disease kill me or am I going to let the system—the police?” Hayes continued, “And if something is going to take me out when I don’t have a job, which one do I prefer?”1

Grappling with these types of predicaments and discerning a personal preference prompts an endless scouring of information. The images, messages, sounds, and signals—part electrical, mechanical, and biological—that connect people to an environment become an indispensable resource for trying to come up with some sort of accept-able answer when asked,

Would you prefer to be killed by a pandemic or continue to suffer from a lack of income?

Would you prefer to be injured by police during a protest or on your walk home?

Information is harvested and mined up-to-the-minute, modifying behavior to the point of mania. Dancing Mania, the social simulation application by Hito Steyerl, explores social unrest by modeling the spread of this mass mania via the demand for information—of the type produced by news outlets, social media, 4chan message boards, and online multiplayer video games, amongst other platforms. This demand for information, manifesting as repetitive body movement—whether it be the synchronized “doomscrolling” of a news mobile app, the rhythmic button-pressing of video game play, or a dancing mania—is amplified by compulsion loops that continuously increase information during social, political, and health crises.

What is a Social Simulation

Social simulations, commonly referred to as agent-based models, are often used in behavioral science studies and take many forms. Sometimes the models are crude, animated graphs—brightly colored dots scrambling like television static. In other versions, the models resemble a video game with miniature avatars, or “agents,” jostling through a small doorway to test emergency evacuation scenarios. No matter the form of the agents, their movements are dependent on a set of controls that change their behavior: parameter sliders labeled as quantified social interactions that help calculate potential scenarios. These models, based on game theory, can simulate energy consumption, hunting patterns, environmental impact, infection rates, ethnic segregation, or, as seen more recently, COVID infection rates in supermarkets.

Social Choreography

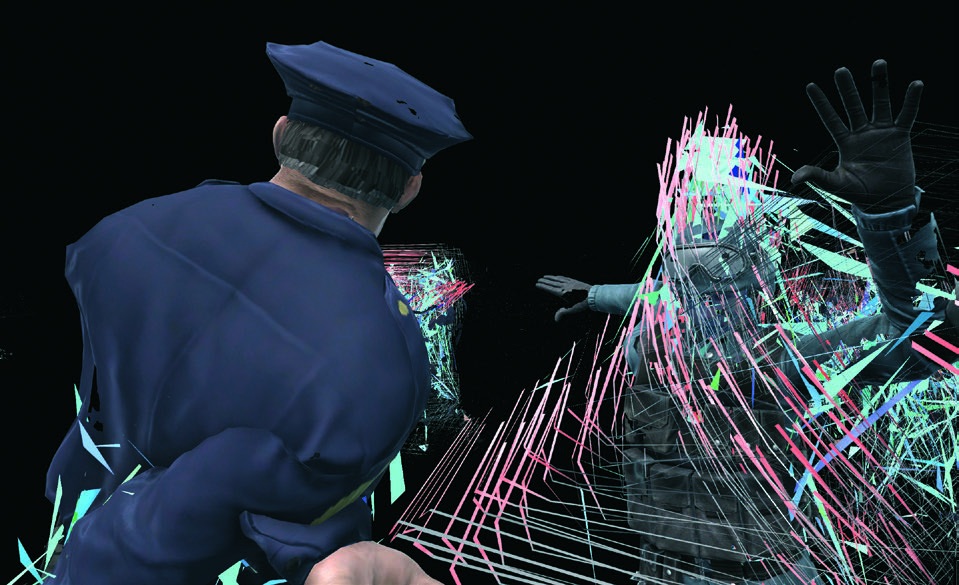

Material from Dancing Mania, 2020

Dancing Mania is loosely based on “civil violence” models by Joshua M. Epstein, professor of epidemiology at New York University. Epstein’s models compute the outcomes and duration of a rebellion using parameters like government legitimacy, grievance, and deterrents.2

By rejecting Epstein’s parameters, the calculations found in Steyerl’s model instead visualize rebellion as a social choreography between rebels, police, and civilians. In representing the institutions of law enforcement agencies and prisons, the social simulation presents itself as a mirror of real, unacknowledged, or implicit values within society, thereby actively contradicting the idea that we already live in a simulation controlled by sinister exterior forces. From The Matrix to Elon Musk’s eccentric ranting that we likely live inside an alien computer, the fear that our agency is an illusion and reality is determined by metalevel controllers is pinned on theories that life is inexplicably getting worse and whoever is in charge cannot figure out how to debug the malfunctioning simulation.

On the one hand, such theories are indistinguishable from conspiracies and contribute to the proliferation of alternative realities. On the other hand, in a more practical sense, simulations have left computers long ago and now take place in real life, or “IRL.” The glitching simulation tormenting us is not Baudrillard’s Manichaean world but an essential, generative tool of governance.

In-the-wild Testing

After World War II, simulations were established as a reliable tool in meteorology and have since been used in a growing list of wide-ranging disciplines as the primary instrument for experimental research. Today’s research methods are less isolated—testing now happens “in-the-wild” with usability research pursued under real-world conditions in order for digital products to be continuously updated. Real-time information flow from these updates through the wide proliferation of digital networks has transformed society into a social laboratory.

Sociologists Noortje Marres and David Stark argue that in such a laboratory it is the “very fabric of the social that is being put to the test.”3 They trace a history of IRL environments as testing sites by harking back to ideas disseminated by the Chicago School and one of its founders, Robert E. Park who, in the 1920s, developed studies that used the city of Chicago as a test site for his research on race relations and what he referred to as “human ecology.”

Since the heyday of urban sociology, the distinction between the “testing environment” and “reality” has all but collapsed with digital applications. For example, today’s political consultancy firms and their data analysis strategies prove that the role simulations play in politics goes beyond merely predicting outcomes to bring about unforeseen circumstances with significant geopolitical repercussions.

In 2014, the Facebook app “thisisyourdigitallife,” which was presumed to be a psychological test that scored “personality types,” was used by Cambridge Analytica to build models based on user profiles to associate them with specific political identities based on their personality.4 The models, which were used to target potential voters on the social media platform, may have had far-reaching effects by possibly enabling both the UK’s exit from the European Union and Trump’s victory in the 2016 US election.5

Epidemiological modeling for the COVID-19 crisis relies on similar social media monitoring strategies.6 As countries initially lacked the resources for medical testing, many people, above all healthcare and other essential workers, felt that they were being used as human sensors. In lieu of lab testing, authorities needed to monitor people falling ill to pinpoint infection clusters. Public-health officials resorted to tracking “sick posts” using social listening software like Synthesio, which specializes in analyzing social media in order to help “rationalize consumer motivation.”7

In addition to Synthesio, infection-tracking efforts also include Fleming, a mobile application developed by NSO, the Israeli firm that has previously been accused of making spyware for authoritarian governments to monitor human-rights activists, including Jamal Khashoggi, the journalist who was murdered in 2018.8 The software, currently being tested by over two dozen governments, tracks when a person (or “target,” as described in the application) comes into contact with a potentially infected person, and based on the duration, location, and time, the likelihood of infection transmission is scored.9 Healthcare is thus substituted for unwarranted surveillance that ultimately benefits the mobile application market.

The exploitation of unknowing people to study sickness for commercial ends has a long history, in which the horrific case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment cannot be overlooked.10 Beginning in 1932, researchers recruited hundreds of Black men in Alabama to take part in a study by promising free healthcare. Roughly two thirds of the participants had syphilis but were not aware of their diagnosis. Instead of receiving treatment for the disease, the unwitting men were secretly monitored until they died and their bodies could be examined for research.

If this seems like a depraved version of the urban sociology practices that emerged in the early twentieth century, it may be because the aforementioned Robert E. Park, of the Chicago School, had previously worked at the Tuskegee Institute and was known to refer to the city of Tuskegee as a “rural laboratory.”11 It goes without saying, however, that any sort of scientific or clinical value pertaining to such a “laboratory” should be reframed as a violently exploitative biotechnological experiment.12

When details of the Tuskegee experiment became public in 1972, the exposure of the medical establishment’s deep deception resulted in long-standing mistrust of mainstream medicine by the African American community. This mistrust was so significant that it undermined public-health education efforts to limit the spread of HIV decades later.13 Paradoxically, the suspicion surrounding “in-the-wild” research leads to the inflation of an infosphere that thrives on dis-information.

Infodemics

Beyond the realm of unethical medical research, this paradox helps to understand a broader, more pervasive vicious cycle: seeking more information for answers to try to understand a crisis causes more information to be produced—the overabundance of which includes misinformation, conspiracy, and hate speech—ultimately causing chaos, confusion, and a demand for even more information.14

The daunting task of dealing with the complexity of interrelated crises has seen people revert to creating their own alternative realities—usually reductive, gamified versions of the world built using the aesthetics of metrics, statistics, analysis, and projections in order to offer solutions and, in some cases, to make a profit.

Take for example, the cryptocurrency CoronaCoin, which purports to “raise awareness” by tracking the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak. CoronaCoins will decrease in supply when people die from the virus, making the remaining currency more valuable. Essentially a bet on the probability that infections are increasing, CoronaCoin is a nefarious investment opportunity masquerading as an altruistic, analytical solution to the pandemic.15

Examples like CoronaCoin may explain why contemporary global crises go hand in hand with information excess. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, noted as much in February 2020 when he declared that “we’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic,” and that fake news “spreads faster and more easily than this virus.”16

Compulsion Loops

An infodemic starts at the interfaces of screen-based media applications. These interfaces are designed by prioritizing addictive mechanics generated by the basic unit of social media: the notification. Whether it be a vibration or message slinking into view, the notification always promises information. The smartphone, using its alert techniques on a variable reward schedule, has the average person picking it up fifty-eight times a day for about a total of three to four hours.17

The addictive mechanics of information are built upon compulsion loops, the foundation of video-game design. These loops are a series of actions that, when repeated, not only produce a neurochemical reward but also generate more information circulating in the world. As doomscrolling the news establishes itself as a daily routine, every new headline will be a cue to generate more headlines.18 Interface design employs the most basic of economic models in which a rising level of news also includes an increase in conspiracy—easy-to-understand narratives that attempt a totalized and distorted vision of the world.

In writing about contemporary forms of conspiracy, James Bridle, in New Dark Age, points out that the compulsion loops of infor-mation production reveal “more and more complexity that must be accounted for by ever more byzantine theories of the world.”19 As a result, conspiracies, according to Bridle, have to account for this increasing complexity by becoming “more bizarre, intricate and violent to accom-modate it.”20

That violence reveals itself when followers of the burgeoning QAnon conspiracy theory go to extreme lengths to gain access to information. Such was the case in 2018 when a man armed with an AR-15 style rifle, in a standoff with police at the Nevada-Arizona border, demanded the Justice Department inspector general’s report on the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server.21

QAnon takes advantage of a generative capacity to latch onto news events in real time. Its success can be attributed just as much to the failure of news to alleviate the anxiety of people trying to identify causes and solutions for crises, paving the way for racism and scape-goating to become a mainstream resource.

Misinformation is Mainstream

The coordinated timing of misinformation, coupled with xenophobic speech, is crucial. Its spread relies on synchronizing with real-world events. Anti-Chinese slurs on 4chan and Twitter ramped up when the WHO declared a public-health emergency, and when Trump began referring to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus.”22

This coordination is yielding more intense results. The Network Contagion Research Institute, a New Jersey–based not-for-profit that tracks hate speech across social media, published a report in April 2020 detailing the increasing “vitriol and magnitude of ethnic hate” as the pandemic spreads. When hate speech, identified in the report as “weaponized information,” increases on less moderated platforms like 4chan, it also begins to surface on mainstream platforms, where the growing presence of conspiracies offered a calculated solution to the pandemic. Crawling out from the remote corners of the Internet onto Instagram feeds, and other social media, this “weaponized information” calls for mass violence. A now-deleted post from “antiasiansclubnyc,” for example, read, “Tomorrow, my guys and I will take the fucking guns and shoot at every Asian we meet in Chinatown, that’s the only way we can destroy the epidemic of coronavirus in NYC!”23

Information Management

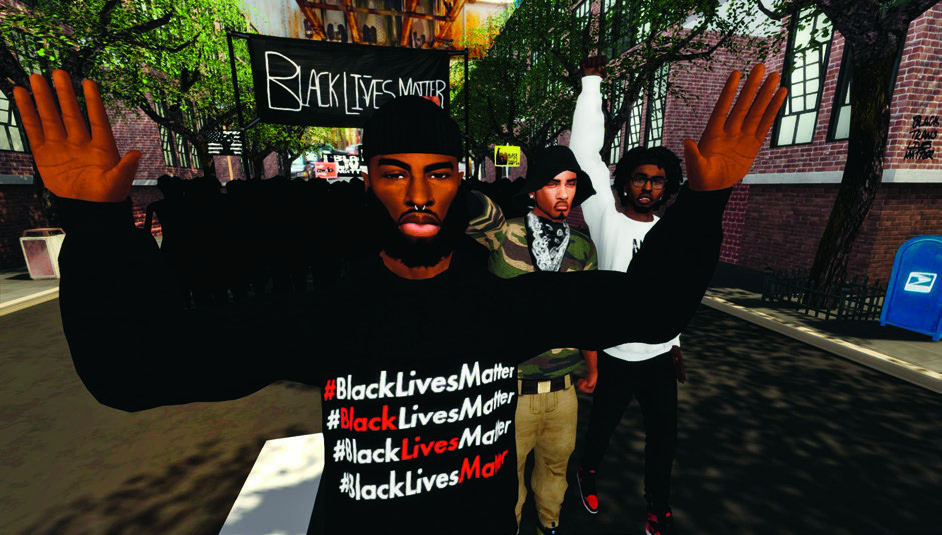

Misinformation becoming mainstream is certainly due to people spending more time online. But these circumstances have also given rise to virtual demonstrations, particularly in video games. A BLM rally in The Sims was recently attended by more than two hundred people, and Animal Crossing suddenly became the site of frequent pro–Hong Kong democracy demonstrations.24 Historically, however, new channels of information flow, once unlocked and solidified, also grant repressive governments and law enforcement new methods of monitoring and control.

A picture from the Black Lives Matter Sims rally tweeted by Ebonix in gratitude to those who took part

A screenshot of Hong Kong protest on Animal Crossing: New Horizon tweeted by Joshua Wong

As the video conferencing application Zoom rose in popularity at the beginning of the pandemic, it came under scrutiny for misleading its users by misrepresenting its claims of end-to-end encryption.25 A few months after these reports, Zoom was accused of censoring users. In June 2020, the company shut down accounts belonging to activists and protest leaders in Hong Kong and in the United States, some of whom were hosting public talks and online events commemorating the Tiananmen Square massacre. Around the same time, Zoom doubled down by only offering end-to-end encryption to paying customers. Eric Yuan, the company’s CEO, told investors: “Free users—for sure we don’t want to give (them) that, because we also want to work together with the FBI, with local law enforcement, in case some people use Zoom for a bad purpose.”26

Long gone are the days of hole-and-corner security officers huddled around a table steaming open envelopes. Technology companies are now openly working with governments to offer widespread, instantaneous monitoring that uses significantly fewer resources. And as governments continue to bungle their responses to the pandemic, technology companies have stepped in to compensate for their failures. As a consequence, social movements will need to confront accelerating methods of surveillance in which information management becomes subsumed under an existing, yet growing pattern of “activist tracking.”

At the height of the BLM demonstrations, Dataminr, a US artificial intelligence firm that boasts real-time detection of “high-impact events and emerging risks,” worked closely with Twitter and police across the country to closely monitor the protests. The startup, with the ability to scan every public tweet, collected social media content to present police with instant reports offering locations, activities, and developments of protests as they were happening.27

Although widely circulated information, like phone footage of police brutality, has helped mobilize protests, advanced surveillance tactics are using the same technologies to quell social movements and, at times, anticipate their formation with predictive policing strategies that depend on social media content.

Stan-tactis

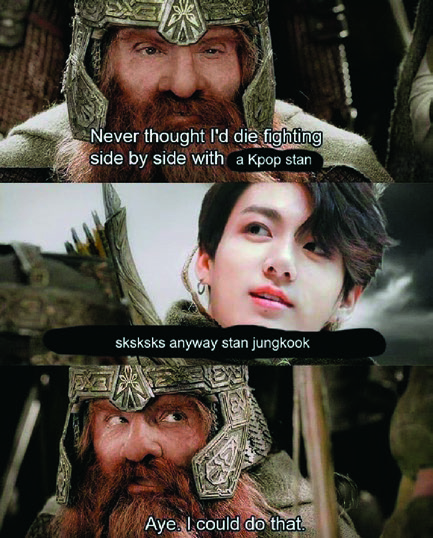

The Dallas Police Department, seemingly lonely on May 31, 2020, tweeted at 1:48 a. m. asking people to send vids—specifically documentation of “illegal activity from the protests" that they wanted uploaded to their new app iWatch Dallas.28

K-pop fans, or “stans,” swiftly took to the pranking opportunity by flooding the request with fancams of K-pop performances. With the reporting system overloaded and jammed, the police department was forced to take down the application.

The shutdown of iWatch Dallas was soon followed by the stans’ manipulation of the Trump Tulsa rally ticketing system through similar techniques. While this highly mobilized strategy demonstrates the power of stan-tactics, other information-jamming efforts have been less effective. In another protest, a deluge of K-pop content mocking “#WhiteLivesMatter,” helped push the hashtag into Twitter’s “Trending Topics” sidebar, which read: “Trending in K-pop: White Lives Matter.”29

What started out as a slapdash strategy to use the hashtag ended up aligning K-pop with what it was protesting against. This goes to show that information technologies are so automated and controlled that even when pushed, they can reset themselves by circulating confusing and contradictory narratives.

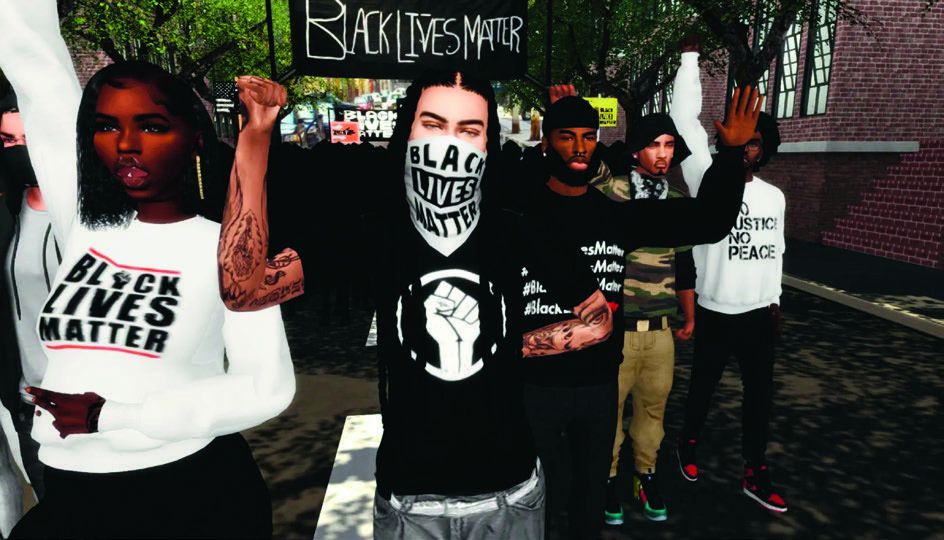

Jung Kook, a vocalist in the Kpop band BTS, and Gimli, from The Lord of the Rings, declaring a common enemy

A screenshot of K-pop stan @skzjennie tweeting on May 31st, 2020

Everybody Dance Now

The case of the squandered “#WhiteLivesMatter” prank demonstrates that automated information channels create what Shoshana Zuboff has termed the “economies of action”—iterative systems designed to intervene in real time and modify behavior toward guaranteed commercial outcomes.

In her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Zuboff outlines three approaches to the economies of action that modify behavior: “tuning,” “herding,” and “conditioning.” While tuning and conditioning have direct roots in well-known behavioral science approaches, herding is more unique to context-aware data. With its focus on controlling an environment, this particular approach “enables remote orchestration of the human situation, foreclosing action alternatives and thus moving behavior along a path of heightened probability that approximates certainty.”

With this in mind, herding starts to resemble the police tactic of kettling, whereby protesters are surrounded and blocked from leaving an area.30 Both herding and kettling are meticulously designed to predict behavior by engineering the environment and eliminating the possibility of self-determination. And, like kettling, herding modifies real-time actions in the world through ubiquitous intervention. Information circulation starts to mirror crowd control, as both rely on the operations of automated behavior. In an interview with Zuboff, a software developer taking the role of a pied piper, explained that in orchestrating this behavior, they are, so to speak, “learning how to write the music, and then [they] let the music make them dance.”31

Dancing Fever

As legend has it, the Pied Piper arrived in the rat-infested town of Hamelin, in medieval Germany, and offered to exterminate the pests by luring them with music into a nearby river to drown. Yet after completing the job, the town refused to pay for his services. The piper then sought revenge by playing another tune, one that hypnotized the children of the town to follow him into the mountains, never to be seen again.

In 1884, Emma S. Buchheim, in an issue of Folk-Lore Journal, suggested that the disappearance had nothing to do with a hypnotizing pipe player. Instead, the children were struck by dancing mania, “a strange psychological epidemic” that spread across Europe, primarily between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries.32

Dancing mania and its variants—“dancing plague,” choreomania, St. John’s or sometimes St. Vitus’s Dance—all refer to the same phenomena in which people would dance hysterically in large groups, sometimes for weeks at a time, and often to the point of death.

The mass psychogenic illness was an epidemic, spreading in crowds that numbered in the hundreds, and sometimes thousands. Those afflicted with the disease would dance to the point of exhaustion and, after falling to the ground, “complained of extreme oppression, and groaned as if in the agonies of death.”33 If people managed to survive, they would pass out, only to wake up and start dancing all over again.

At some point, it was believed that people under the spell would stop dancing if they were to hear music. Yet not unlike the vicious cycle of information demand—in which seeking information produces more information—the music remedy backfired: once musicians starting playing, more were encouraged to join in the dancing.

In the exhibition Hito Steyerl. I Will Survive at K21, the social simulation Dancing Mania rearticulates the phenomena of dancing mania by visualizing a social choreography; one in which the movements are amplified by the production and circulation of information—and the increasing demand for it—within the context of the pandemic and continuing unrest.

The parameters of Dancing Mania are adjusted daily during the course of the exhibition by the NGO Forum Democratic Culture and Contemporary Art. The adjustments account for real-time changes in the local prevalence of irrational and authoritarian tendencies as expressed by pandemic deniers, right-wing law-enforcement networks, and conspiracy- and horseshoe-theory proponents.

The simulation’s parameters track tendencies that underlie local social responses to crisis. These include:

- Death Threats Sent from German Police Servers (per Day)

- Identitarian Jealousy Factor (per Cultural Appropriation)

- Manic Denial Spread (per Sentiment)

- Kanye Complex (New Infections per Day)

- Cancel Culture Efficiency (“0”)

- Diverted Commando Ammo (in tons)

- Support for Horseshoe Theory (per Mounted Police Squad)

- Days Left to Day X (per Day “0”)

- Blame Soros Constant

The simulation essentially cracks open the black box of digital herding and kettling to reveal the technological parameters used to regulate, control, and disrupt society.

You don’t have a job. You only have two options.

Would you prefer to die by: Disease? Lack of Income? Starvation? Police? Dancing?

The only possible multiple-choice option is YES.

Material from Dancing Mania, 2020

Rebellion

Dancing Mania will be supplemented by a standalone application launched at Centre Pompidou titled Rebellion. Returning to Joshua M. Epstein’s “rebellion” model, which is, by design, a never-ending loop of oppression and protest, the parameters of the new application—based on historical contingencies that reject conspiracies and their alternate realities—generate a rebellion to succeed. Rather than a tool to predict the future, this social simulation is thus reformulated as an instrument for analyzing (and potentially recalibrating) the present with new parameters:

Would you prefer to model society based on:

The Survival of the Fittest or Social Solidarity?

Public Services or Private Interests?

The Economy or Human Well-Being?

The answers could even include NO.

Notes

Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “‘Pandemic within a Pandemic’: Coronavirus and Police Brutality Roil Black Communities,” The New York Times, June 7, 2020.

See Joshua M. Epstein, “Modeling Civil Violence: An Agent-Based Computational Approach,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), May 14, 2002.

Noortje Marres and David Stark, “Put to the Test: For a New Sociology of Testing,” The British Journal of Sociology 71, no. 3 (June 2020): 423–43, here: 423.

Carole Cadwalladr and Emma GrahamHarrison, “Revealed: 50 Million Facebook Profiles Harvested for Cambridge Ana lytica in Major Data Breach,” The Guardian, March 17, 2018.

Jane Mayer, “New Evidence Emerges of Steve Bannon and Cambridge Analytica’s Role in Brexit,” The New Yorker, November 18, 2018.

Jobie Budd et al., “Digital Technologies in the Public Health Response to COVID-19,” Nature Medicine 26 (2020): 1183–92.

John Scott Lewinski, “Synthesio Brings COVID-19 Social Media Monitoring into Graphic Focus,” Forbes, April 21, 2020.

Craig Timberg and Jay Greene, “WhatsApp Accuses Israeli Firm of Helping Governments Hack Phones of Journalists, Human Rights Workers,” The Washington Post, October 30, 2019.

Kareem Fahim, Min Joo Kim, Steve Hendrix, “Cellphone monitoring is spreading with the coronavirus. So is an uneasy tolerance of surveillance,” The Washington Post, May 2, 2020.

Deneen L. Brown, “‘You’ve got bad blood’: The Horror of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment,” The Washington Post, May 16, 2017.

See Robert E. Park’s introduction to Charles Spurgeon Johnson’s Shadow of the Plantation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934).

Benjamin Roy, “The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment: Biotechnology and the Administrative State,” Journal of the National Medical Association 87, no. 1 (January 1995): 56–67.

See Marcella Alsan and Marianne Wanamaker, “Tuskegee and the Health of Black Men,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133, no. 1 (February 2018): 407–55; Gina B. Gaston and Binta Alleyne Green, “The Impact of African Americans’ Beliefs about HIV Medical Care on Treatment Adherence: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Interventions,” AIDS and Behavior 17, no. 1 (January 2013): 31–40.

This point is based on James Bridle’s formulation of network excess generating a feedback loop that results in failure to comprehend a complex world. See James Bridle, “Conspiracy,” in

New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (London: Verso, 2019), 187–214.

Anna Irrera, “CoronaCoin: Crypto Developers Seize on Coronavirus for New, Morbid Token,” Reuters, February 28, 2020.

Department of Global Communications, “UN Tackles ‘Infodemic’ of Misinformation and Cybercrime in COVID-19 Crisis,” United Nations: COVID-19 Response, March 31, 2020.

Adrienne Matei, “Shock! Horror! Do You Know How Much Time You Spend on Your Phone?,” The Guardian, August 21, 2019.

Brian X. Chen, “You’re Doom scrolling Again. Here’s How to Snap Out of It,” The New York Times, July 15, 2020.

Bridle, New Dark Age (see n. 14), 188.

Bridle, 205.

Mike McIntire and Kevin Roose, “What Happens When QAnon Seeps from the Web to the Offline World,” The New York Times, February 9, 2020.

Leonard Schild et al., “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: An Early Look on the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19” (2020).

Savvas Zannettou et al., “Weaponized Information Out break: A Case Study on COVID-19, Bioweapon Myths, and the Asian Conspiracy Meme,” Network Contagion Research Institute (2020).

Daisy Schofield, “Black Lives Matter Meets Animal Crossing: How Protesters Take Their Activism into Video Games,” The Guardian, August 7, 2020.

Micah Lee and Yael Grauer, “Zoom Meetings Aren’t EndtoEnd Encrypted, Despite Misleading Marketing,” The Intercept, March 31, 2020.

Nico Grant, “Zoom Transforms Hype into Huge Jump in Sales, Customers,” Bloomberg, June 2, 2020.

Sam Biddle, “Police Surveilled George Floyd Protests with Help from Twitter Affiliated Startup Dataminr,” The Intercept, July 9, 2020.

Accessed August 20, 2020, https://twitter.com/DallasPD/status/1266969685532332032.

Kaitlyn Tiffany, “Why Kpop Fans Are No Longer Posting about Kpop,” The Atlantic, June 6, 2020.

Ali Watkins, “‘Kettling’ of Peaceful Protesters Shows Aggressive Shift by N.Y. Police,” The New York Times, June 5, 2020.

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2019), 294.

Emma S. Buchheim, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” The Folk-Lore Journal 2, no. 1 (1884): 206–9.

Justus Friedrich Carl Hecker, The Epidemics of the Middle Ages, trans. B.G. Babington, 3rd ed. (London: Trübner & Co., 1859), 81.